Bridging the Gap Between Operations and Optimization- Part 1

My work puts me at the intersection of optimization and operations on a daily basis. While I consider this a tremendous privilege, it can also be a lonely place from time to time. On one side I have all of the people, thoughts, and ideas about how to make a process optimal, and on the other side, all of the people, thoughts, and ideas about how to simply get it done. Often these two sides disagree, and will frequently try to limit there involvement with the other side. Being in the middle puts you in a position of trying to help both sides and being welcomed by neither.

Take for example a situation where there is an active water leak in a building. In the moment what you ultimately want is the shortest possible time from recognition of the leak to the supply being shut down. This is the operational perspective. We have a goal, minimize the problem, and we want to do that as quickly as possible. When you take this view it is easy to see how an operational perspective would lead you to value institutional knowledge above all else. After all, if you know that building inside and out and know exactly where the valve is and how to get there, the getting there and turning the valve is usually the trivial part.

In general, the operational perspective values institutional knowledge as being of the highest value. By institutional knowledge I mean those hard earned lessons that were purchased with time. The way that you know that preset button #4 on your radio always has to be pressed twice for some unknown reason– institutional knowledge. Knowing that a damper has to be manually adjusted during start up because the startup program will fault out– institutional knowledge. Where the water shutoff valve is on the third floor of the building where you have an active water leak– institutional knowledge.

I'm going to try and convince you that relying on institutional knowledge is a bad idea. What I will not argue is that it isn't valuable. Make no mistake, having someone who knows exactly where to go and what to do is EXACTLY what you need in that moment, and if you have that, you have the silver bullet. My argument is going to be largely based around the fragility of reliance on institutional knowledge.

The optimization perspective comes with a more generalized approach. I typically start by assuming that at some point we will be completely reliant on someone with no institutional knowledge and no access to someone with institutional knowledge. This is absolutely a worst case scenario, but money is made/saved or lost in the worst case scenarios. So on the optimization side we start from the point of requisite skills – that is to say that all we assume we have to work with are the general skills of a competent person in a position. A qualified mechanic on day one in a new facility has only the general skills of a competent person. They know how to turn off the valve if you show them where it is, but at this point they don't even know where the bathroom is.

Trying to determine what to do about this situation is where the two schools of thought start to have disagreements. The operations side tends to say, "I have someone with the institutional knowledge so my path forward is to have them work with someone new to pass on that information." This is how it has been done for decades and how many things will continue to be done, but you can see how fragile this is. What if the person with the knowledge quits suddenly? What if their retirement sneaks up before they were able to pass on the majority of the information?

The optimization camp starts in at this point looking at tools and references. What could we give the new person on day one that would enable them to perform like they have been around for years? We do this intuitively with things like phone numbers: here is your list of numbers for the people you may need to call. It may be that after 10 years on the job you have every number memorized and call from memory, but with that simple contact sheet, someone on day 1 is only a step behind. They know where to go to get the information they don't know.

While this seems intuitive in one domain, phone numbers, once we shift domains it seems less and less apparent that the approach holds value. You start to see arguments like:

- There is too much information to try and build a reference tool.

- We don't have time to build a reference tool.

- Nobody uses these references anyway.

- It's too complex to explain. The only way to learn it is to be part of it.

What you may notice is that none of these arguments are based on disproving the value of the reference tool, but instead, all of these attack the feasibility of building a reference. This I would argue is a cop out. It's akin to saying, "We know this would be valuable, maybe even invaluable but it's just too hard." Try that next time your boss asks you to do something of value, acknowledge the value but say it's just too hard to capture that value.

The operational side also has an argument that has been an "ace in the hole" for many years now: operations never stop. Any effort that you dedicate to building a reference tool is time you are taking away from doing the very thing you want the reference tool to be used to do. I've heard something to the effect of, "Do you want me to do the work or do the paperwork?" more times than I can count. It's an effective argument in that it frames an abstract benefit, some unknown quantity of future benefit, in terms of a concrete loss now: each hour I spend working on this reference is one hour I don't spend on work orders. Effective it may be, but a shortsighted argument nonetheless.

So how do we think about the cost of reliance on institutional knowledge? I propose the "On Deck Metric." On Deck? It's a way to think about the vulnerability of a process by looking at the rate of change of the outcome as performed by the different people who may have to perform the task.

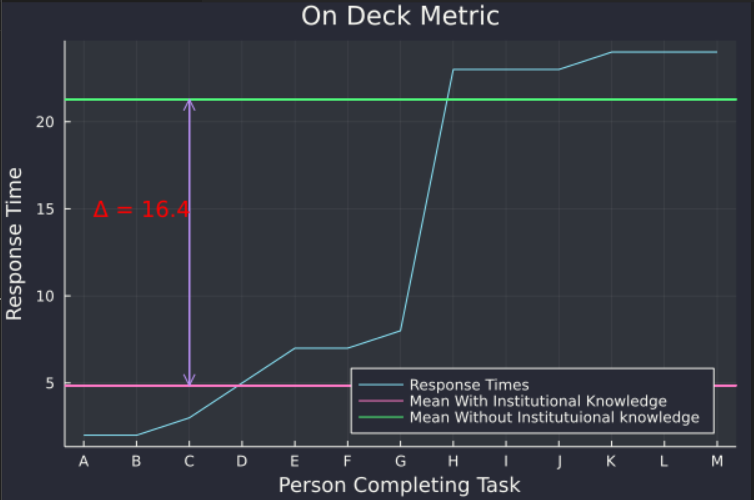

I define the on deck metric as follows: the time difference between the mean time to completion of a task for a group with institutional knowledge and a group without institutional knowledge assuming the same general qualifications.

Take the example below where a group of people A-M all have the same minimum competency qualifications. A-G are your seasoned veterans who know the place inside and out, they have institutional knowledge. H-M are your others who have the general skills, but not the same institutional knowledge. The difference between the means of these groups is the on deck metric.

I call this the On Deck Metric because it looks at the fall off between your last best hope to complete the task and the next person up, aka "on deck." This is a way of taking the bad situation and pushing it one step further and asking, "What would we do if {Insert Person Here} hadn't been able to come to the rescue?"

I think there is a tendency to equate trying to prepare everyone to respond effectively to trying to negate the value of those who can respond quickly on account of their knowledge. Nothing could be further from the truth. Building the necessary reference tools is an attempt to cap potential losses by setting the floor on what can be expected for response. It says nothing about moving the ceiling. In fact I think we should encourage the use of institutional knowledge to speed and improve outcomes. We shouldn't however be reliant on it.

With that I'm going to wrap up part 1. In subsequent installations we will take a look at what we can do to try and meet the needs of current operational demands while also building foundational tools for optimizing performance in the future given that we know much less about the future than we do about today.